Read the whole article

the exhausted

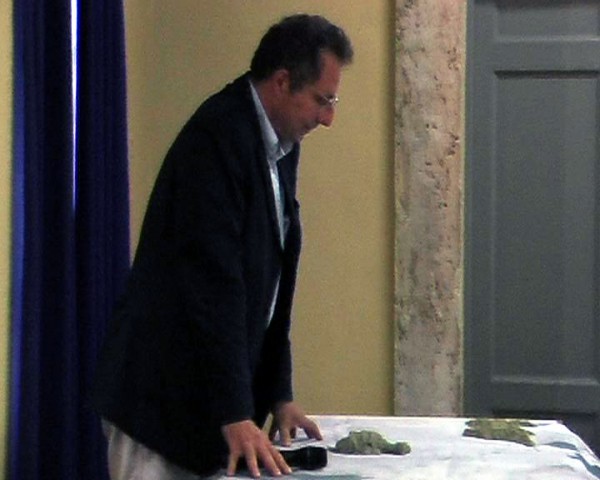

At a meeting during the conference on the metropolis held at the Faculty of Architecture of Roma Tre University, Mauro Folci presented a performance, L’esausto (The exhausted), for which an Architecture professor of the faculty, Francesco Ghio, accepted the challenge set by the artist and played the role of an exhausted man who has also exhausted his power of speech. Sitting at a desk with a map of Europe over which a clay reproduction of the donkey Balthazar lies dying, the exhausted tries to speak into a microphone and take the floor, but cannot utter or finish a single sentence. The exhausted is left with no breath to articulate sounds into words. After several attempts to address a speech to the astonished audience, the exhaustedis thrashed by a group of children emerging from a side door, who shout words from a passage in Beckett’s Westward Ho!: Less best. No. Naught best. Best worse. No. Not best worse. Naught not best worse. Less best worse. No. Least. Least best worse. Least never to be naught. Never to naught be brought. Never by naught be nulled. Unnullable least. Say that best worst. With leastening words say least best worse. For want of worser worse. Unlessenable least best worse.

In Mauro Folci’s performance, the characters of the donkey and of the architect are not accidental. As a symbol, the donkey has always been rather ambiguous, and both demonised and deified in the Christian tradition. If its hooves, its mundane character have confined it to the sphere of evil figures, its Christian qualities and its endurance of heavy work have pushed its image towards a symbolism closely related to the divine. Bresson’s donkey fully embodies these two

meanings: from happy beginnings through outright adoration, the donkey ends up being exploited to exhaustion only to die in a valley surrounded by a herd of sheep, killed by accident by a gunshot fired against smugglers. The donkey however, once its Christian virtues of long-suffering and humble endurance of pain are laid down, is the penultimate figure. Following Nietzche, in Mauro Folci’s vision, death is not the reversion to inorganic matter, but a chance for

transformation and transmutation of values which the donkey takes upon itself. The donkey must die in order to be born again. He must take on chance as if it were a divinity and an opportunity to say yes to life, a yes that might wish for more of the same again.

Also Nietsche’s donkey, in Zarathustra, is molded on Christian symbolism. However the philosopher’s donkey represents Nihilism, being capable of saying nothing but ‘yes’ (I-A) and bearing the heaviest burdens. The donkeys’ ‘yes’ must change into the Dionysian ‘yes’, since the former is simply the hypocritical acquiescence of people who can’t say no. Mauro Folci’s performance combines the figure of the donkey with that of the architect, dumbfounded in front of the desolate map of Central Europe over which the dead donkey lays. A maker of both material and conceptual constructions, the architect represents the failure of modernism and its sinking into western Nihilism: he is attacked by a group of children reminiscent of the Nietzschean child, a key figure to overcome reactive Nihilism. Mauro Folci’s work is based on Deleuze’s The Exhaustedabout Beckett, a borderline figure that insists on exhausting all that is possible. The theme of exhaustion (exhaustivity) in Beckett’s work: does not occur without a certain physiological exhaustion (Deleuze,1999), according to Deleuze. To be exhausted is different from being tired.Being tired is the result of striving to pursue an objective,whereas the exhausted is exhausted by nothingness. Any action undertaken from a range of possibilities would amount to expressing a preference or setting oneself an aim. In fact, the exhausted no longer has any preferences, objectives or needs. ‘Being exhausted is not the same as being tired. Whilst the first has renounced any preferences, the second still has the strength to lie down and sleep, to set himself an aim; the exhausted has exhausted everything and sits down with hands and head in a little heap. (Ivi, 13) Far from doing nothing however, the exhausted must deal with many useless things and their segmentation in space and time. His gestures do not come from need or a particular purpose or meaning: in the exhausted there is an exhaustion of all that is possible through meaningless plans and schedules. For him, what matters is the order in which he does what he has to do, and in what combinations he does two things at the same time when it is still necessary to do so, for nothing. (Ivi, 13)

The exhausted architect does not even manage to start talking, whether because he is not confident enough or perhaps because he has too many plans and schedules which appear meaningless to him just as he is about to begin. Mauro Folci’s exhausted is also disoriented, and evokes the image of human beings as neotenic, i.e. a chronic child who never learns, whose existence becomes a continuous process of learning and mutation.

by Marta Roberti: Working Whilst Talking, Talking Whilst Working. Language at work in Mauro Folci’s art.

Elglish translation: Valentina Mazzai

(…) After several attempts to address a speech to the astonished audience, the exhaustedis thrashed by a group of children emerging from a side door, who shout words from a passage in Beckett’s Westward Ho!: Less best. No. Naught best. Best worse. No. Not best worse. Naught not best worse. Less best worse. No. Least. Least best worse. Least never to be naught. Never to naught be brought. Never by naught be nulled. Unnullable least. Say that best worst. With leastening words say least best worse. For want of worser worse. Unlessenable least […]